Not that I think it's my God-given duty to size up the Finals and decide who's up, who's down, but you've got to admit that Lakers/Magic does present a certain number of curious proposition. For one, these two are neither mismatched nor equals. It's like they exist in parallel universes. The Lakers, as we all know, as flushed to the gills with ability, but only periodically harness it all. The Magic, well, we didn't realize it until recently, but so are they. And they bring it on the regular. Does that make Orlando overachievers, Los Angeles underachievers, and no one but the Cavs the underdogs? The Magic's has been a season of peaks and valleys, hitting their stride, then losing Nelson, then picking up steam again, then hitting a wall earlier in the playoffs when Howard's identity came into question and Turkoglu was hurt. And now, they're riding high, so high, again. The Lakers? Friday was the first time all playoffs they've looked like the Lakers we expected to see come and visiti pestilence upon the postseason. Now you tell me: Which is inconsistency, which on a voyage of self-discovery and perpetual adjustment?

What's more, while this series doesn't seem to have STAR BATTLE written all over it, it will certainly challenge the "nobody digs Goliath, ya dig?" axiom of the modern NBA. Because, simply put, Howard is love and lightness, Kobe the darkest side of Jordan, the least ecstatic aspects of his game, streamlined and boiled down to something potent, metallic, and kind of smelly. That's not to say that Kobe's still the man we love to hate, just that he'll never be easy to love—in much the same way that Chamberlain, and even Shaq, found themselves troubled by.

Here's some fragments from a piece I wrote this spring on Shaq for a certain well-known web magazine. This was from draft #3, and apparently wasn't snappy enoigh. So sorry, guys. In any case, I think it's pertinent here for describing just how far Howard is indeed with "the new Shaq," in terms of natural magnetism and ability to worm his way into our hearts without making us feel engorged or cloyed by absurdity:

O'Neal wouldn't be the first athlete always angling for the spotlight, or looking for ingenious forms of self-promotion. But compared to, say, the whip-smart expressiveness of Muhammad Ali in his prime, O'Neal is at once light-hearted and uncomfortably deliberate. He excels at spoken spectacle, assigning himself absurdist nicknames (my favorites: The Diesel, The Big Aristotle, and Shaqovic) and making off-color jokes about opponents, like his disparaging reference to rivals "the Sacramento Queens."

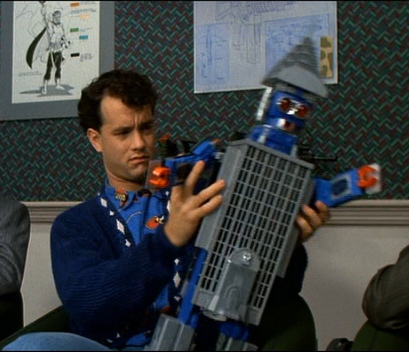

From the beginning Shaq saw himself as an entertainer, which explains 1993's platinum rap album Shaq Diesel and film roles ranging from the 1996's Kazaam, in which Shaq played a genie, to 1994's Blue Chips, an underrated look at corruption in college sports that starred Nick Nolte. The more he does, the more control he exerts over his image. And with good reason. In the fraternity of superlative NBA big men, O'Neal stands alone in his non-stop levity. Wilt Chamberlain, Bill Russell, Kareem Abdul-Jabar, Patrick Ewing, and peer Tim Duncan, to name a few, were pensive and aloof—and often criticized for it. O'Neal has seemingly spent his entire career trying to break the mold, replacing the towering, faceless Goliath with a hip-hop Paul Bunyan. Shaquille O'Neal may have been Joe Frazier or (young) George Foreman on the court, but preferred the garrulous, daft Ali role off of it.

However, this disconnect comes with a price. Shaq's behavior can get downright ugly when his ego, image, or brand are threatened, since this could send him plummeting into in the annals of large, bitter, awkward freaks. For evidence of this, look no further than the litany of "sidekick" guards who have proved essential to his success: Penny Hardaway in Orlando, Kobe in Los Angeles, and Dwyane Wade in Miami. In the post-Jordan NBA, smaller, more dynamic players are the unquestioned center of attention. Style-wise, they're the Ali's, with inventive games that suggest a richness of personality. Shaq, always the talker in these relationships, always casts himself as the alpha dog, a font of charisma whose dominant play was a matter of fact. At the same time, in each case the other guy was emerging as one of the most exciting, inventive players in the league, leading O'Neal to turn cold and toward them, and however incidentally, move on to another team. [I think you all know how Shaq fell over, and then turned on, Penny, Kobe, and Wade].

Nothing sums up this paradox more than the mural on the bus Shaq brought to an LSU game in 2007: some sort of gangster super-summit, where Shaq presides over Scarface, Tony Soprano, and Vito Corlene, among others. Hilarious, but also quite sinister. Not coincidentally, during his time with the Heat, Shaq was fond of an analogy that cast his Hardaway as Fredo, Kobe as Sonny, and Wade as Michael. Coppola's films and The Sopranos have been defanged by their absorption into pop culture. But watch those movies from start to finish, and you'll realize just how unsettling they really are.

Heavy, huh? Man, been waiting for a while to get that out. I have to say, though, that this series might explode this paradigm, and perhaps summarily frustrate Shaq's grand mission in life. Despite O'Neal's attempt to undermine Howard, or Howard's obvious inferiority as a pure center—perhaps one of the reasons this slippage is possible—Dwight, with his boyish good looks and effortless acrobatics, is that lovable big men Shaq never could be. Yes, we can debate for days when he is in fact a big man, or just a bigger Amare. But the Superman has stuck there without any sense that we're being forced into embracing his might (like how Superman really could have destroyed the world whenever he wanted). On the other hand, Kobe, while he remains the epitomal post-Jordan off-guard, we all know that this trappings of his game have become so methodical, his aura so admirably bleak, that it's transformed the dream-like "as an explosive shooting guard, I will get rings" of Jordan into a optimization of the position so that it embraces as much of the big man rigor as is possible. LeBron is unstoppable, quasi-religious. Kobe is so professional that he's always adjusting, a character who is about as Terminator-like as guards can possibly get. Like when they made the evil robot a hot lady for T3.

That's not to say that Kobe lacks charisma. He has kind of reached that rare, glare-laden apex where, no matter what his game has evolved into over the years, or what its finer points are, fans respond to him as a showman. You and I know, though, that the man is probably replacing his blood, or grafting metal onto his spine, in hopes of turning this positional role into something with the certainty, and even the purposeful vacancy, of the big man. Howrad is so young, it's hard to gauge where he's really headed. But for now, he's a hunk of muscle unstoppable down low who is also so easy to love. And it's Kobe whose human drives and expressions of self seem more of a technicality or, even to supporters like myself, an afterthought in his grand pursuit of basketball perfection. That's not to say he's totally inhuman, on or off the court, but the personality of his position (and by extension, the Good Kobe that has so many fans) is no longer a restriction on how he looks to put together grade-A efforts.

And to turn briefly to one more WTF about this series: Does this tell us shit about the future of the game? The Lakers are by no means a reasonable template for success. Top to bottom, that team is loaded. In ways new and old. What other team can boast one of the league's most promising pure centers, as well as its second-best Euro, and a post-Garnett weirdo—all who may or may not figure prominently into the game-plan on any given night? It's almost like a brief history of the last eight years of the NBA, all on one team. Except that participation by all is optional, or maybe selectively minimal. Put simply, other teams have no chance at copying this one, and that's without even getting into Kobe's embattled, but persistent, standing among the league's elite.

The Magic offer a far more interesting case. They have this big man who is both more and less than the past. There's a chance they stumbled into it, and that the tandem of Lewis and Turkoglu are both essential and came as a surprise. And when healthy, they have an All-Star point guard. This is old worship of height, plus the age of the point guard, plus a kind of post-Euro Sudoku puzzle that only master coach SVG could make sense of in such a non-obvious fashion (and, as Kevin Pelton has pointed out, this team would suck if deployed in obvious fashion). I also pick up a distinctly Pistons-meets-Suns vine int he way Lee, Pietrus, and even Reddick are used, though maybe now I'm just laying it on thick. In short, this team has everything but a Kobe or LeBron, which is a really fortuitous spot to be in. And chances are, any other squad with this roster would screw it up. So we might be looking at an utter singularity here that both bridges and invalidates the entire ferment of conventional basketball wisdom, past and present. In the end, it comes down to the twist you put on it. Traditions and trends, new and old, can tell you some basics, but past that, you're on your own. The question is, what does it take for a team like the Magic to be absorbed, as the Suns were? The Warriors certainly weren't . .

Orlando Magic, just keep being yourselves. History will sort out the rest. As will the results of this series, incidentally.

No comments:

Post a Comment